Tags: Corporate governance

In order to thrive in the long term, businesses need to gain the trust of the communities from which they draw their employees and customers. One key way that organisations can seek to gain this trust is through increased openness and transparency, albeit recognising that total transparency is not practical or feasible in all circumstances.

An organisation that is open and honest about its financial performance and ethical credentials can expect to enjoy a greater degree of trust. We should be wary, however, of transparency for transparency’s sake. To make a real difference to trust and accountability, information needs to be concise, coherent and to the point, avoiding information overload.

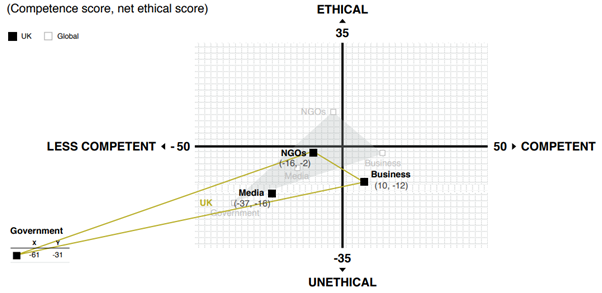

The recently published 2019 edition of the IBE’s Attitudes of the British Public to Business Ethics survey found that 57% of people believe that business as a whole tends to behave ethically. This represents a 5-point decrease on the 2018 figure of 62%. The latest edition of the Edelman Trust Barometer also reflects quite poorly on the state of trust in British business. The graphic below shows the performance of four key institutions (business, government, NGOs and media) on two crucial determinants of trust (ethics and competence).

Image credit: Edelman 2020

In the UK, business was perceived as unethical, but narrowly achieved a low positive score on competence. This was a better performance than the other three institutions, but hardly a ringing endorsement. Crucially, at both the UK and global levels, none of the four institutions were seen as both ethical and competent.

Edelman research indicates that competence is the less important of these two determinants of overall trust, accounting for 24% of measurable trust capital. Meanwhile, 76% of trust capital hinges on ethics-related dimensions. In other words, ethics is three quarters of trust.

Increased openness and transparency is commonly proposed as a policy response to all manner of problems, in accordance with the old chestnut that ‘sunlight is the best disinfectant’. It follows from this assumption that trust in the ethical credentials of business could be improved with greater transparency around issues such as workforce diversity and environmental impact.

However, it must be stressed that information should be communicated intuitively and intelligibly for transparency to be effective. In some cases, transparency measures can provide effective solutions in themselves. In other cases, they might provide us with useful information which we can use to decide next steps. Other times, they may not make much difference at all.

Transparency guarantees the disclosure of information, often in huge quantities. It does not guarantee that the information will be accurate, well-presented, coherent or intuitive. It may amount to little more than noise, useless for informing policy decisions. The challenge here is to avoid ‘information overload’ while ensuring all stakeholders have quick and easy access to key figures.

For this reason, standardised disclosure frameworks are an increasingly appealing proposition. For example, the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development suggests employing a ‘People Reporting Framework’ to improve the quality of workforce reporting. Such a framework would set out key metrics and performance indicators related to employee satisfaction, retention, productivity, diversity, and other related variables.

Standardisation of this kind improves the interpretability and usefulness of data. It also allows much easier cross-comparison between organisations. Simultaneously improving the quality and quantity of information disclosed makes companies both more accountable and more able to identify and address flaws in their operations. Some organisations are already realising the business benefits of reporting on non-financial indicators like environmental sustainability, productivity and employee satisfaction. A review of UK listed companies found that the average FTSE350 firm uses 9 KPIs, of which 3 are non-financial.

Measuring ethical culture as a whole, however, is extremely challenging, particularly for companies with a large number of employees across geographical locations. Group-wide KPIs do not differentiate between what is happening in various parts of the business. Boards need to be able to disaggregate data sufficiently to get a picture of discrepancies in culture between different parts of the business.

There are a number of methods or indicators that are used to produce quantitative data on culture. Most common amongst these are employee surveys. A great advantage of these in comparison to other measures is that they are a form of self-reporting. A great deal of workforce disclosure is made up of reporting on people, rather than reporting by people. Boards can gain a more genuine picture of the culture of their company by asking the employees who work in various parts of the business, rather than by looking at statistics on, for example, staff turnover rate or number of Speak Up calls, which have to be very carefully interpreted, and whose usefulness is severely limited without the inclusion of accompanying contextual information.

We do not just need more trust; we need organisations to be more genuinely deserving of trust. Meaningful, metrics-driven transparency around ethical culture can go a long way towards achieving this by ensuring businesses are more accountable and better equipped to make good decisions.

The status quo seems to be for companies to publish vast amounts of over-engineered financial performance data while neglecting culture monitoring. This is not just negligent towards ethical responsibilities and towards stakeholders, it is a real business mistake. After all, ethics is three-quarters of trust, and a trusted business is much more likely to generate sustained long term value for all.

Author

William O’Connor

Researcher, IBE, [email protected]

As a Researcher at the IBE, I contribute to a wide range of research projects and publications, carry out advisory work for supporter and non-supporter organisations, and assist in the delivery of events and training.

I joined the IBE in October 2019 as an intern after concluding my studies for an MA in Corruption and Governance at Sussex University. After 3 weeks as an intern, I became a permanent member of staff at the Institute.

Integrity has no need of rules – Albert Camus