Tags: Corporate governance, Ethical Values

Read Prof. David Grayson's blog for Board Intelligence.

It seems as if rarely a week goes by, without the pages of the Financial Times, the Wall Street Journal and other business media across the world, reporting on the latest examples of businesses and business people behaving badly, and being unethical. Whether it is fraud, bribery, corruption, bullying, sexual harassment or worse.

No board, no CEO, no Senior Management Team (SMT), no Strategic Business Unit (SBU) head, no Private Equity owner, no majority shareholder can guarantee that their business or their part of the business will behave ethically 100% of the time. Businesses are, after all, communities of individuals. Sometimes these communities will include individuals who are happy to behave unethically, or who are negligent or cavalier about doing so.

Business psychologist Merete Wedell-Wedellsborg, in a blog for the Harvard Business Review website (The Psychology Behind Unethical Behaviour, April 12, 2019), highlights three psychological dynamics that can lead people to cross ethical lines:

First, there’s omnipotence: when someone feels so aggrandized and entitled that they believe the rules of decent behaviour don’t apply to them. Second, we have cultural numbness: when others play along and gradually begin to accept and embody deviant norms. Finally, we see justified neglect: when people don’t speak up about ethical breaches because they are thinking of more immediate rewards such as staying on a good footing with the powerful.

Sometimes, individual employees may honestly believe that they are making the ethical call on what is an ethical dilemma – but who afterwards are judged to have made the wrong call.

Whatever the motivation, ethical lapses can and do happen. So, if leaders cannot guarantee 100% adherence to desired ethical standards, what can they do to minimise the risks of unethical behaviour? For be in no doubt, there are significant risks. Various recent cases have demonstrated the reputational, financial, market, operational and other risks of unethical behaviour – especially if this is egregious and repeated over time. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Businesses and other organisations (whether in the public sector, Civil Society etc) can reduce the likelihood of ethical failures and rebound better if ethical failures have occurred, if they have taken the time and made the effort to build and maintain an ethical culture.

That is to say, an organisational culture where everyone knows how they are expected to behave and are helped to resolve ethical dilemmas, for example, with ethical decision-making models and tools. Such organisations also promote a “speak-up” culture, which calls out questionable behaviour before it gets to the “nuclear option” stage of whistleblowing.

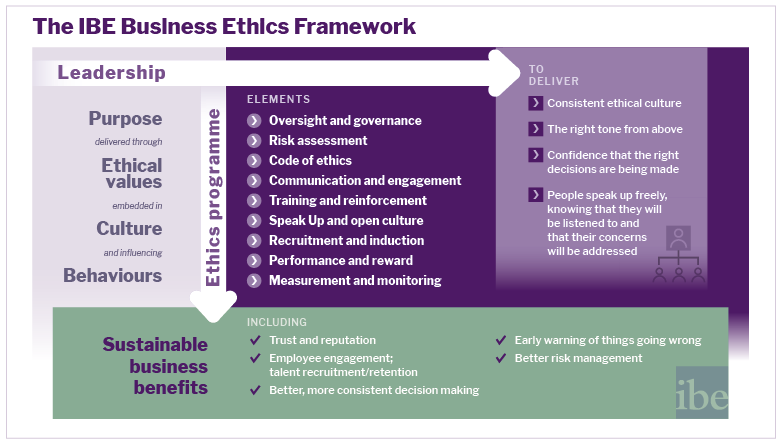

Drawing on nearly forty years of working with businesses, the Institute of Business Ethics has developed and recently refined an Ethical Business Framework. This starts with clarity about organisational purpose and values, and being clear about how all employees are expected to behave in their dealings with each other as well as with customers, suppliers, business partners, competitors and other stakeholders.

Generally, it is helpful if there is a Code of Ethics or a Statement of Business Principles – as long as this is a living document, which is meaningful to, and understood by, employees. This requires regular socialisation through induction, team briefings and refreshers. It needs leaders at all levels talking about how the Code has helped them resolve ethical dilemmas – and demonstrably “walking the talk” themselves, in how they behave. This also requires linking ethical behaviour to rewards and recognition. Beware organisations which nominally have a Code of Ethics but then reward so-called “super-star” employees “who get the business done” irrespective of how they do so. See Figure 2 IBE Business Ethics Framework.

Figure 2.

Boards and SMTs etc should want to reassure themselves that they have each of the building blocks of the IBE Business Ethics Framework in their organisation (or satisfied themselves that a particular element is really not relevant in their particular circumstances).

In order to help boards fulfil their governance and oversight responsibilities, the IBE has just consulted on guidance for boards about building and maintaining an ethical culture. This has been developed with the help of highly experienced NEDs and chairs from a range of PLCs and other major businesses. The guidance was published in final form at the beginning of October. We have been clear throughout, that this guidance should be relevant and highly accessible to board members. Its tone is intentionally practical and advisory rather than “preachy” or overly prescriptive. And the advisory group overseeing the development of the board guidance insisted it was kept to two sides of A4! It is guidance from experienced NEDs and chairs for their peers.

The IBE is enormously grateful to the advisory group overseeing this project and to everyone who responded to the consultation over the summer. Please now help us to publicise this guidance. If you serve on a board or support the work of a board, please get the guidance on to the board agenda for a frank discussion. And please do let us know how your board(s) reacted. The advisory group for the project has kindly agreed to reconvene in a year, to review reactions to the IBE Board Guidance, how it has been used and what kind of impact we have achieved with the guidance.

Author

Professor David Grayson CBE

Chair

David is Emeritus Professor of Corporate Responsibility at Cranfield School of Management. From 2007-2017, he was director of the Doughty Centre for Corporate Responsibility and Professor of Corporate Responsibility.

David became Chair of the Trustees Board on 01 April 2019.

He joined Cranfield in April 2007, after a thirty year career as a social entrepreneur and campaigner for responsible business, diversity, and small business development. This included founding Project North East which has now worked in nearly 60 countries around the world; being the founding CEO of the Prince's Youth Business Trust and serving as a managing-director of Business in the Community.

David has an Honorary Doctorate of Law from London South Bank University and was a visiting Senior Fellow at the CSR Initiative of the Kennedy School of Government, Harvard (2005-10).

He has served on various charity and public sector boards over the past 35 years. These have included the boards of the National Co-operative Development Agency, The Prince of Wales' Innovation Trust and the Strategic Rail Authority. He chaired the National Disability Council and the Business Link Accreditation Board; in each case appointed by the Major Government and re-appointed by the Blair administration. David now serves on the board of a financial services company in Asia where he leads on embedding ESG/sustainability and chairs the board’s Group Risk Management Committee.

He has previously chaired the national charity Carers UK and one of the UK's larger social enterprises and largest eldercare providers, Housing 21 during which the organisation made corporate history by becoming the first-ever not-for-profit successfully to acquire a publicly quoted group of companies. David received an OBE for services to industry in 1994 and a CBE for services to disability in 1999. He is a Companion of the Chartered Institute of Management.

David has written a number of books on responsible business and corporate sustainability including most recently: ‘All in - The Future of Business Leadership’ and The Sustainable Business Handbook – both with Chris Coulter and Mark Lee. He is part of the faculty of the Forward Institute and of the Circle of Advisers for Business Fights Poverty.

The Guardian has named David as one of ten top global tweeters on sustainable leadership alongside Al Gore, Tim Cook - CEO of Apple, and Facebook's COO Sheryl Sandberg.