Tags: Code of Ethics

For more than 30 years, the Institute of Business Ethics (IBE) has been advocating for the use of codes of ethics, as a way of communicating a company’s value principles to their stakeholders. Since then, we have been tracking the trajectory of corporate codes and advising organisations on how to develop and embed high-quality ones.

Our research series on ethics policies and programmes found that, according to senior ethics and compliance professionals, the primary purpose of a code is to create a shared and consistent culture and to provide guidance to staff. As such, modern codes should be created to support the achievement of these objectives.

Our research on the codes of ethics of FTSE 350 companies found that just 57% of publicly available codes meet the standard the IBE would consider as 'good'. In essence, a lot of corporate codes lack qualities that guide employees towards a shared and consistent culture.

So, what qualities make a high-quality code?

Based on our research and advisory expertise, the IBE framework for code review contains four broad dimensions, each with respective sub-elements:

- Leadership endorsement: This dimension assesses whether the code is championed by senior leaders, embedded in management practice, and regularly reviewed and updated

- Speak up culture: Under this dimension, the code is evaluated on its provision of clear, robust mechanisms for raising concerns, and declaration of unequivocal commitment to non-retaliation

- User-friendliness: The code is assessed on ease of navigation and visual engagement, and provision of ethical decision-making frameworks for addressing workplace dilemmas

- Nature, language and tone: This dimension focuses on whether the code avoids legalistic jargon, and instead uses accessible, engaging natural language that denote a shared responsibility for ethics.

Codes that score highly on these dimensions do more than set boundaries for employees and other code users such as suppliers; they inspire trust, empower decision-making and signal a genuine commitment to ethical conduct.

So, focusing on the fourth dimension, how can a code be engaging in terms of its nature, language and tone?

Language for creating a culture of shared responsibility

Based on IBE’s rich history researching and reviewing codes, we know that the earliest versions of codes of ethics often contained lists of rules and dos and don’ts. Today, as expectations on businesses have increased, so have the objectives for creating and embedding codes. Modern codes have evolved into values-based frameworks, articulating not just what is allowed, but what is expected, encouraged and celebrated within the business.

Despite the best intentions, many organisations unwittingly undermine their own efforts with the language in the code. When codes are dominated by legalistic, authoritarian phrases such as 'you must' or 'you must never', they create a sense of distance and obligation. Codes that refer to 'staff', 'employees' or 'personnel' create an artificial divide between the organisation and its people.

In contrast, the use of positive, collective language in codes, such as 'we value', 'our standards', or 'we act with integrity', reinforce the notion that from the boardroom to the shop floor, upholding ethical standards is a shared responsibility.

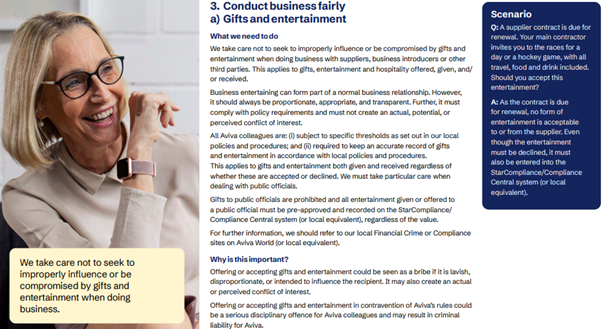

Good practice example 1

Extract on gifts and entertainment guidance in The Aviva Business Ethics Code 2025 – living our values. This shows examples of the consistent use of positive, collective language about upholding standards in a code

Language for enhancing clarity and accessibility

Clarity is paramount. High-quality codes are written in simple, concise language, free from jargon and ambiguity. When codes are easy to understand, they are more likely to be used as intended: as practical guides for decision-making, especially in situations where the right course of action is not obvious.

It may be necessary to get a bit technical when discussing certain issues in a code, so tools that support simple language are essential for crafting good codes. Comprehension aids such as question-and-answer boxes, FAQs, and scenarios, bring the code to life, making it relevant and memorable. These features move the code from the abstract to the practical, demystifying expectations and empowering employees in taking the correct action.

Good practice example 2

Extract of conflict of interest guidance in Phoenix Group: Our Code of Conduct. This example highlights how comprehension aids can be used to simplify jargon and provide practical guidance. Also, note how the language on the ‘consequence of ethical breaches’ focuses on the organisation’s responsibility to external parties, instead of language focused on 'disciplinary action' only

Language for demonstrating leadership commitment

Good codes include genuine and consistent language on leadership commitment to upholding the set standards (‘acting as role-models’). This is important for demonstrating tone from the top, giving employees assurance that everyone (including senior leadership) is accountable to the standards set by the code.

The IBE generally recommends that codes include signed statements, written in personal and engaging language by the leadership team e.g., CEO, and/or Board Chair or Head of Ethics. This statement should reiterate the role of the code as a driver of a shared culture, stress the importance of a speak up culture, and contain an unequivocal assurance that anybody who raises concerns or reports misconduct in good faith will not experience retaliation for doing so.

Good practice example 3

Extract of leadership statement in Bank of England: Our Code. This example shows how language can be used to denote leadership commitment to values, shared responsibility, speak up and non-retaliation

The key takeaways

- High-quality codes are written in positive, collective language that reinforces the notion that upholding ethical standards is a shared responsibility

- High-quality codes include comprehension aids that support the use of simple language that demystify expectations and empower employees to take the right action

- High-quality codes include genuine and consistent language on leadership commitment to upholding set standards and a safe, non-retaliatory speak up culture.

Conclusion

Humans are natural storytellers, so language has immense power on our emotion and brain. By harnessing the power of language, business leaders can create codes that move beyond legal-sounding documents to ones that help satisfy the demands of the modern business era. Modern codes not only set the boundaries of what is allowed but also explicitly showcase what is celebrated and valued, guiding employees towards an ethical culture.

Author

Dr Samuel Tosin Lawal

Researcher

As a Researcher at IBE, Sam plays a crucial role in supporting the development, delivery, and dissemination of both internal and external research and advisory projects. Sam's passion lies in harnessing the potential of both quantitative and qualitative data to foster a culture of ethical considerations within business practices and policies, ultimately contributing to a broader societal impact.

Before joining IBE, Sam held the position of Research Officer for the University of Reading's Research Culture Project. In this role, he led research initiatives aimed at enhancing the research environment within the university. Additionally, Sam worked part-time as an Associate Lecturer at Henley Business School, where he delivered Undergraduate Business modules and supervised Master's dissertations in Marketing.

Sam holds a degree in Accounting from Babcock University, Nigeria, and an MSc in Business Analytics and Management Science from the University of Southampton. Notably, in 2018, he secured the prestigious Henley Business School Marketing and Reputation PhD Scholarship. This accomplishment led to the successful completion of his PhD in Marketing and Reputation from the University of Reading, where his thesis investigated the malleability of public attitudes and behaviours to organisational stories incorporating stakeholders' perspective.