Tags: Corporate governance, Speak Up, Ethics Programme issues

As we launch Embedding Business Ethics: 2020 report on corporate ethics policies and programmes, the ninth in this triennial series, listen to Guen Dondé, IBE Head of Research and author of the report, discuss some of the most interesting findings with IBE Researcher Will O’Connor and IBE Research Director Simon Webley in this IBE webinar.

Here's a selection of some of the questions asked during the webinar:

How have the survey questions changed over time, and has the focus of the survey shifted in any way?

I would say that the survey has expanded rather than shifted its focus. The earliest editions almost exclusively revolved around Codes of Ethics, which is still a major component, but the scope of the research has widened to include more elements of ethics programmes over time, such as Speak Up programmes, board engagement and training to name a few.

When we were looking back at the 1995 survey, we noted that there was a section featuring arguments put across by senior executives as to why they shouldn't bother with a Code of Ethics. That in itself is an illustration of how much perspectives have shifted since then; not many CEOs would want to publicly state how proud they are that they have little or no ethics programme in their organisation.

The research shows that there has been a shift from an approach based on rules to one based on values. Is there any examples that you can share to illustrate this evolution of codes, based on IBE's experience in doing code reviews for organisations?

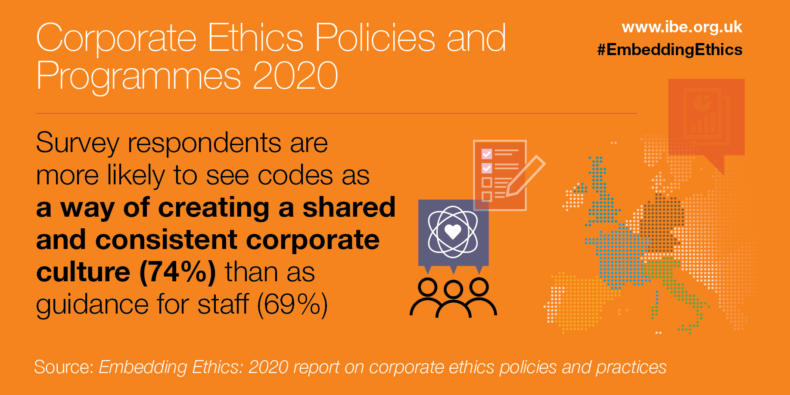

One of our key findings is that organisations primarily see Codes as a means of creating a shared culture. This reverses a long-term trend of Codes primarily being seen as a source of staff guidance. In terms of how this shift manifests itself, in our recent advisory work we've noticed many organisations place a lot of emphasis on using engaging, inclusive language, avoiding legalistic jargon and lists of ''do's and don'ts''.

We've also had a lot of organisations express interest in decision-making models, which we are very pleased to see. These decision trees are almost emblematic of the shift from guidance to culture; more than ever, organisations realise that Codes and policies cannot provide clear guidance for every possible situation, so they want to develop tools that equip people to make informed choices based on underlying ethical principles.

Desktop research reveals that there are some differences between countries, and in particular the findings reflect relatively poorly on the UK. Can you tell us a bit more about that?

Our desktop research found that just 75% of UK firms had a publicly available Code, 78% had public core values, and 77% discussed ethics in their annual report. This placed the UK last in all 3 criteria.

A couple of caveats, however; firstly, it's not unheard of to have your Code and/or core values as internal documents, so these would not be captured in our research. The IBE encourages making both Codes and values publicly available. Secondly, the data say nothing about the quality of codes. The longest we found was 90 pages and the shortest just one page, so there's a lot of variation in style and level of detail. The average across all 5 countries was around 25 pages. That's not to imply that longer is necessarily better, just that Codes are wildly different. Some are excellent and others less so, but the raw numbers don't capture that.

I would also note that coverage of ethical issues in annual reports tends to be approached in a legalistic, compliance-focused way, rather than a values-based one. This was generally the case in all 5 countries included in the research, rather than a UK-specific trait.

What is the impact of sharing all information gathered about ethics and the effectiveness of their programme with everyone in the organisation?

Generally speaking, the more open you are in your culture as an organisation, the more widely you are able to share issues that come up; if everybody can see what the issues are, it's much easier for them to play their part in addressing them. This makes it easier to fix problems at an early stage, before they escalate and present serious risk to the organisation.

Sharing information with staff is also a part of the shift from rules-based to values-based approaches to ethics. A rules-based approach will simply tell staff what they can and cannot do. If you can show people solid data that drives home why they are expected to behave according to certain principles, and how their behavioural patterns can make a real difference, they will be more engaged and aware of ethical issues. Equally, when senior leadership takes a decision designed to address an ethical concern, they can back up that decision with the data and show the rationale for their actions.

Sometimes that information is confidential, for example Speak Up cases, so it has to be presented in an anonymous way; aggregate data on Speak Up usage rates and the categories of concern raised most often, for example, rather than discussing case specifics which could draw attention to the individuals involved.

Do you have any suggestions for E&C practitioners to engage with board members effectively and make sure they listen?

The person appointed as Ethics and Compliance Officer should have a direct point of contact with the Board, and preferably direct access to the CEO.

We are increasingly seeing board subcommittees focused on making ethics programmes effective, usually chaired by a non-executive director to ensure objectivity. The relationship between the board and the person ultimately responsible for ethics is crucial to maintaining an effective ethics programme; if that person has to go through, for example, the legal department, you'll find that ethics is taken less seriously at board level. So, our strong recommendation is that there should be a direct link to the board and particularly the CEO.

Do you have any thoughts on how useful board-level committees can be, and how companies use them?

The main thing is that these committees get boards talking about these issues where there isn't a right or wrong answer, and which are not covered by law or regulation. Very often, however, the ethics element gets crowded out, because ethical dilemmas are still framed in the context of specific policy decisions. My personal recommendation is that there should be an individual on the board whose focus is on how the organisation does its work. Not what it does, or why it does it, but how. The precise structure and scope of any board level committee they sit on can vary, but the important thing is that there is a strong voice on ethics sitting on the board.

Mind you, there is a big difference between giving someone overall responsibility for matters of ethics (which everyone plays a role in), and simply putting ethics in a box and handing it to one person to deal with so that nobody else has to think about it.

This is particularly important at times of personnel change at board level. Each new member should liaise individually with the individual responsible for ethics to discuss their responsibilities as a board and as an organisation, to ensure a consistent approach to ethics and drive home the message that while one person oversees ethical concerns, every board member has a duty to think about them and factor them into decisions.